On ‘The Sequence Series’ Greg Bryce

(Extracts of this text published in Novelty Magazine, Spring 2018)

The creative urge is something that’s always been of interest to me. Even long before this energy was channelled into making art it was an important part of how I lived and played. The urge to build a fort in your bedroom as a kid is the same urge behind cooking a delicious meal in adulthood. For me It all comes down to potential. The seemingly endless freedom within a given parameter. When I began making sculpture I felt bound to the classic materials of the discipline. Moulding clay, casting plaster, carving wood etc. True expression of my concepts began to come through when I realised the greater potential every day things had for making things with visual originality. The struggle then became how to use found objects in a way that almost simulated craft; conveyed control and familiarity with these materials. However this was also restrictive and had to be let go in order to produce pieces which were more honest, pure and readable on their own terms.

How does this happen?

The limitations of a material must be found and explored. Rules are inevitably formed yes but these rules may only be seen through the actual experience of exploring them. Repetition of common resolutions in forms and relationships appear according to how they behave in my hands. This then gives artworks strength without the reason why being clear. Obviously in using materials such as bricks however, more inevitable results appear. The problem with these types of pieces is the classic argument that it could be ‘art for art’s sake’. Frustratingly, unlike painting, Sculpture and installation is more at the mercy of these questions. The notion that painting could offend is now obsolete. Think back to the likes of Fernand Leger who in the early 20th century flirted dangerously with semi-abstract constructivism for years before taking the dangerous leap into the wholly abstract. In the 1930s an abstract mural of his created such outrage for non representation that it was actually torn down. Challenges against 3D art may be rare but they still occur. So it’s maybe necessary to take a look at how we actually judge an artwork when seeing it for the first time.

Social Context is largely irrelevant. This is something used in hind sight as a way of conveniently categorising the creative development of mankind. And of course for pricing.

How did it came to be (in terms of the idea behind) it is still important. i.e. How did someone come to the decision to put this thing into the world?

The remaining judgement factor is how it was made. Craft and creative flare you might call it. Remember when judging art though, people are usually simply looking for ways in which to talk about it in terms which can actually be communicated and compared.

We are moved by music but seldom discuss the notes. So what are we looking for in these areas? The answer perhaps is energy. Passion. Surely then in judging creative pursuits what we’re judging is creativity itself. This is why that modernist idea of the Genius artist still holds so true in the high end market.

But lets strip this back. Lets throw lego into a room and send someone in to play with it. But lets at the same time either forget what lego is or throw something else in instead. Stones, earth, scaffolding, soap. Lets see what happens fundamentally with materials when no rules exist.

The first thing that will happen to the maker is that these rules I mentioned before will inevitably be formed in order to facilitate experimentation. These will arise from variables read in the limitations of the materials and environment from interacting with the objects and observing the space. Often the materials will be separated into categories or bundled in some way. If the arena is square the corners or the edges may be traced. Perhaps the material will be divided into 4. Geometric patterns tend to be favoured. Circles, cubes, gradients. This comes from how we actually perceive space and form: abstractly. In the minuscule time between gathering information with our senses and projecting them to our conscious mind we read our surroundings as mathematics. As a rhythm of ups and downs, lengths and breadths, similarities and differences. Think about spatial OCD. This comes from how we all view the world; and indeed works of art.

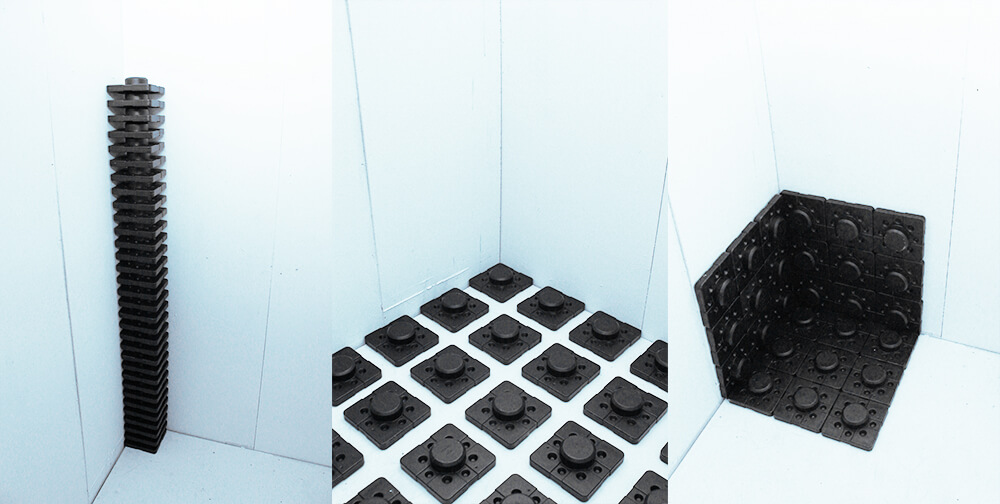

So when I was undergoing this process how would I actually form an artwork such as the series shown? Furthermore why is it worthy of highlighting? For me the interesting observation comes from the landmarks of form which are reached. I would find, looking back later at the photographs I documented when making the installations and even later at the photographs I selected from these, that there would be a preference for strong form which related appropriately to the immediate surroundings. The artworks in this series for a while only really existed as photographs as it allowed the development of the resulting forms to be seen. I then concluded the work by instead building 6 identical rooms which the audience could walk through to flatten the time frame involved in the exploration.

What I’m getting at with these experiments is that we in a way actually become our environment. The world outside is of little use therefore becomes irrelevant. This is active in almost every situation in our lives. We are always ourselves yes, but the wholistic essence of experience is tied directly into what we are sensing. The next step in thinking then is If we were to find ourselves nowhere, what would we be? Without our senses what is left? Simply emotion? Perhaps in some bizarre and unreadable inner landscape of chemicals? Or maybe we are left with our base imagination and desires? Our memories? It’s a pretty dark idea to consider but one which should be; if a phenomenological line of thinking is still of any relevance in art today.